-

Posts

352 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

1

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Gallery

Events

Store

Posts posted by joerookery

-

-

There is a very short new article showing the German tactical symbols used by the great general staff in 1914.

0 -

We have this scheduled as an April title UK, and probably August/September for the USA.This is the timeline from the publisher.

0 -

Thank you! We had no idea – none – that was available. This was all new to us. Publication date, ISBN, price. A hell of a lot cheaper in the US than in the UK. I don't think we're ever going to get any chance to even edit it again. 144 pages. Always good to know what your publishers are doing!

0 -

Thanks! I guess the most telling review was in Stand To! – Our last book is in the pipeline and should be published this coming spring and summer.

IMPORTANT? ABSOLUTELY

Dr. FRANK BUCHHOLZ, Col.(Ret.) Joe Robinson & Col. (Ret.) JANET ROBINSONThe Great War Dawning – Germany and its Army at the Start of World War 1Verlag Militaria, Vienna, Austria, Euros 59.00, 532 pp., 80 ills, two unbound maps/charts.It’s a question a book reviewer is asked all the time; ‘Do you actually read all the books you write about?’ For once I admit - I am about to offer unalloyed praise for a book of which I have read little; indeed scarcely scratched its massive surface. My defence? Few, if any, military works have impressed me as much on first examination and none that I can recall, more. From its table of contents to the last page - 531 -The Great War Dawningis a big book. (Not least both libraries and collectors will need to store in one of those annoyingly unruly ‘oversize book’ shelves where the big books lurk. It is 0.5” high, 7.5” wide and 2 .25” thick. As well as it 500 plus pages of dense, but clear, type it offers numerous charts and seventy-five pages of well-reproduced photographs, maps and illustrations. It contains seventeen chapters, bolstered by seven impressive and valuable appendices - one with eight subsections - and ten closely-spaced pages, all of which bibliography comprise 166 pages.This authors’ tour de force is the definitive work of reference on the Germany’s Army in 1914, and to call it impressive would be a huge understatement. It the most complete work on the subject in the English language, (and probably German). This is no merevade mecum, but, effectively, a one volume library on the topic which also includes a valuable an analysis of the nation’s social, political and economic structure before the war.In addition to an evaluation of the German Army, from its structure and organisation to its officer corps and from its doctrines - infantry, army and artillery – to its material of logistical services,The Great War Dawningoffers critical evaluation of the nation’s plans for war, mobilisation and the ‘cracks’ in its edifice which appeared when Germany sought to execute its plans. Amongst other areas, the appendices evaluate the nation’s Imperial Constitution, the structure and organisation of the Imperial Army in 1914, including that of Bavaria, Saxony and Wurttemberg, the rank and pay structure and the staffs and orders of battle of the German Armies after mobilization.There is no question, the writing team’s research has been massive, their authorship, and the book’s editing, which has enjoyed considerable input from Jack Sheldon, is hugely impressive. No one privileged to receive a review copy of this valuable new work can fail to echo Sheldon’s words in the book’s introduction: ‘This timely and authoritative book should be on the shelf of every serious student of the First World War. I commend it highly and hopethat it will be widely read.’The Great War Dawningwill representa magnificentaddition to my own collection of reference books and one to which I will return with regularity. Despite its cost, it is impossible to praise the work too highly. It is the book of the year about the Great War in 2014 and I suspect for years to come for anyone with a serious interest in Germany and its army in the Great War.David FilsellThis review, written by David Filsell, was first published in Stand To! the Journal of the Western Front Association, No. 101, September 2014. 0

0 -

I know very little about medals but an antique dealer is trying to sell me these two. I think he wants way too much and I don't know what I am dealing with. I think the second one is Bulgarian? Can you help me identify them and tell me anything else about them? Thank you in advance.

.png) Click for large view - Uploaded with Skitch

Click for large view - Uploaded with Skitch.png) Click for large view - Uploaded with Skitch0

Click for large view - Uploaded with Skitch0 -

I think you'll really really like this. The first five chapters are an updated expansion of the last book but then there are 12 more chapters! Like I said weighing in at 4 1/2 pounds if I threw it at you it would definitely make an impression. Like all of his stuff the pictures are magnificent. The product is magnificent. We got a super nice review from Chris Baker but even if it is all nonsense the physical product is so nice. And it's only $70 I'm sure if you have bought from him before you paid twice that. Let me know if it answered any of your mail.

V/R

Joe

0

0 -

Eric,

No. I do not believe there is an English version. Whereas Great War Dawning has no German version. It is only in English.

V/R

Joe

0 -

At some point during the mobilization and move toward France, the German high command apparently decided to shuffle many if not all of the cavalry units.Good morning, I’m sorry I missed this entire thread but better late than never. Not only did they shuffle cavalry units but I think it is a specific story of its own. It is covered in our book Great War Dawning. HKK2 was in the north. HKK-1 was in the South. The reshuffling took place two days after the general advance started. Suddenly the staff realized that they had deployed the cavalry in the wrong place. Their attempt to fix it on the fly was to move HKK1. From an operational perspective this was an absolutely Herculean effort. HK K-1 had to disengage, pull back, turn 90°, conduct a major river crossing, change army headquarters, cross the lines of communications of two complete armies and their logistical trains, and relocate not to the near side of the Second Army but rather to the far side. All of this without any logistical infrastructure above the division level and no radio.

Andy, notice on your map that HK K-1 is missing. Maybe they should of put it in there with the tag “in transit”. This reshuffle – wish I had used that word – took quite some time not surprisingly. When HK K-1 and HK K2 joined together on the right of the second Army I felt that was the end of the dawn for the cavalry.

0 -

To show that there is a silver lining – our publisher Verlag-Militaria just changed their website and added a USA side of the site. What that means to us mere mortals is that you can now order the book from that website in the USA with USA prices, USA money, USA postage. As a result Great War Dawning is only $70 plus postage in the USA. Weighing in at 4 ½ pounds with 80 perfect picture pages [many in color], four foldout maps and 550 pages this is an absolutely handsome work. I don’t make money on this – the publisher does – but this is one hell of a good deal for USA customers. There is a button on the upper right-hand corner of the website:

http://www.militaria.at/Default.aspx

click that and USA customers are taken to a different area from the international site. Not only is Great War Dawning available but it looks like his other books too. As beautiful as this product is you might want to consider it for a Father’s Day present. Seriously nice but I am biased.

0 -

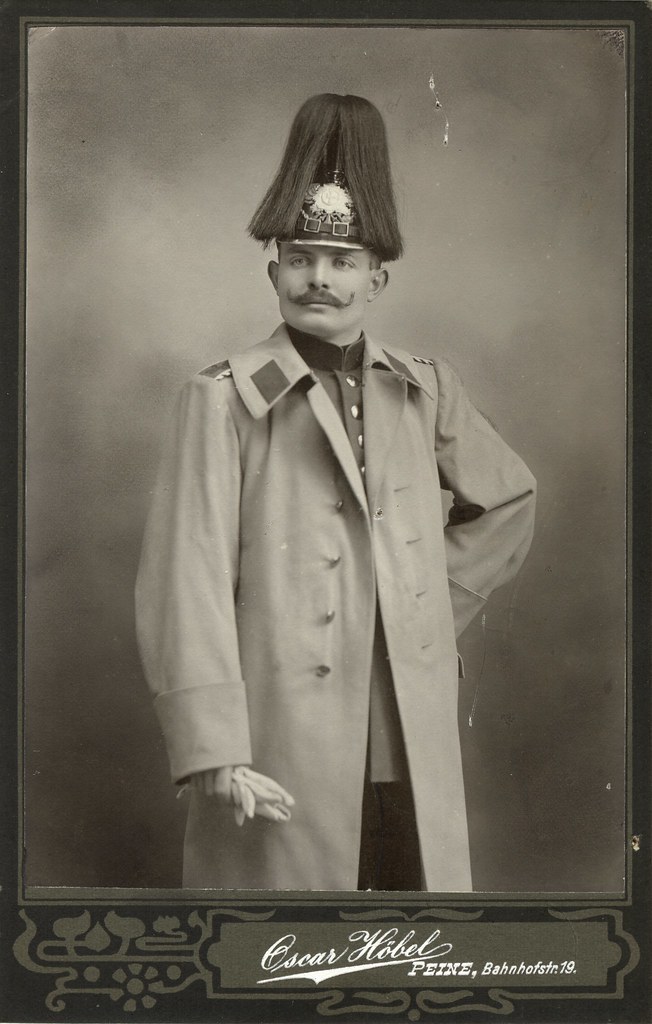

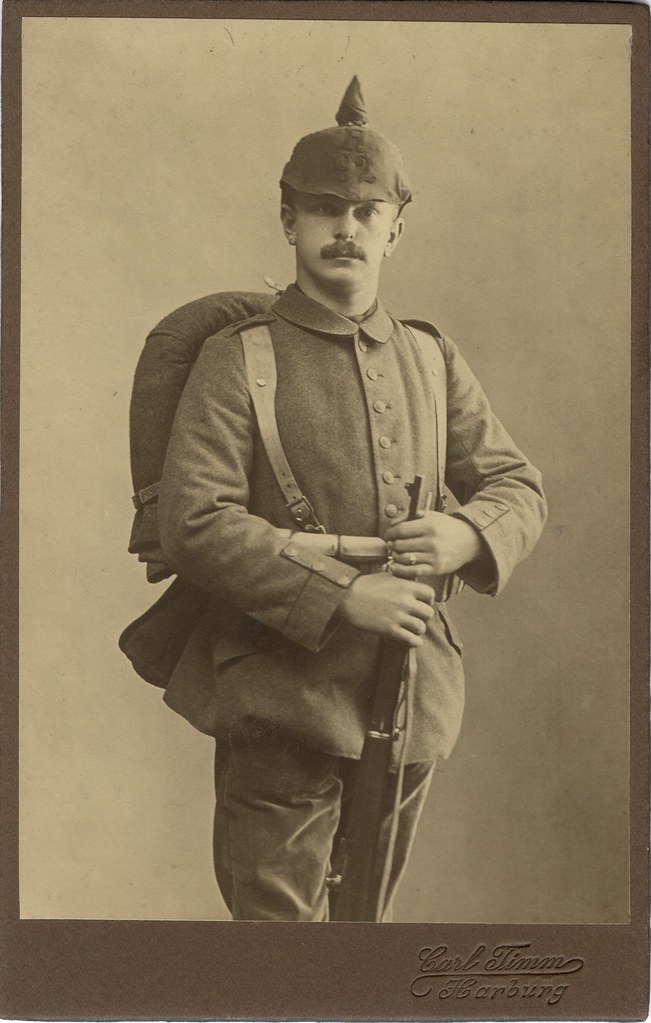

We have quite a few pictures of JR 92. Here are some samples.

ps3034 by joerookery, on Flickr

ps704 by joerookery, on Flickr

ps28 by joerookery, on Flickr

RJR 92 was a different story. Despite the fact that the number is similar it does not look as though these guys had a lot to do with one another.

ps284 by joerookery, on Flickr

0 -

Yes of course! Thank you Andy. I need more coffee.

0 -

Is it possible based on the date that this picture was taken when he was in a junior cadet school? He would have been quite young.

0 -

Thank you Dan! Yes I'm still interested.

0 -

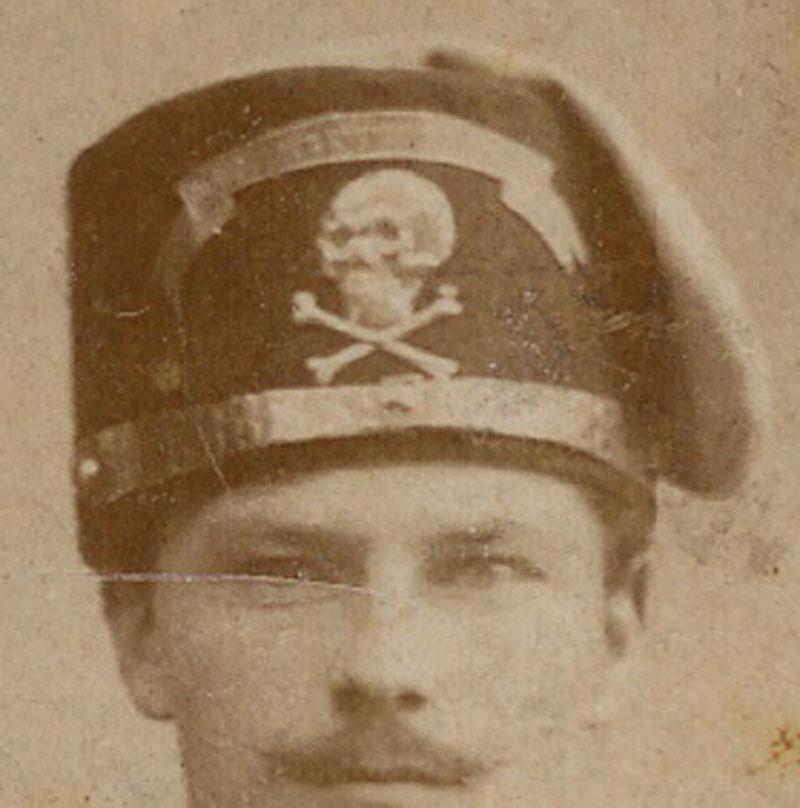

Here is the rest of that photo and a close up. What exactly is this device? This was taken in Spandau.

ps2030 by joerookery, on Flickr

ps2030b by joerookery, on Flickr

0 -

Ulsterman Do you really think that the picture is that new 35-45. It could be because of some very strange anomalies. His helmet is truly weird. But I never even considered a more modern photo. Looking at it I don't think so but we cannot explain much of anything!

0 -

1

-

-

-

I dig these things up just to drive you insane!

0 -

-

Was the officer commissioning process at the time a two-year process? 1 1/2 years? Is this a stupid question because there may have been too many different ways for regular officers to get commissioned, so there really isn't a standard?

The Steps to Becoming an Officer?

As you can imagine, the steps were full of exceptions and changes, all aimed at ensuring the right person was accepted and that the wrong person was not. The basic ten steps to commissioning were similar for both the civilian method, Fahnenjunker, and the cadet schools Fähnriche method. Some steps had more exceptions than others.

Step 1 -- Select a regiment to join

All guard and cavalry regiments actively recruited nobles to keep the regiments pure. A variety of methods were used to lure the young noblemen. They used fancy uniforms and depot locations near fashionable, large towns. Guard and cavalry units could expect additional income of 1000 marks per month for candidates. The more remote, lower-regarded regiments often had problems attracting new recruits. Despite this, they insisted on a rigid class and social pick during step 2.[1] The maintenance of high social standards led to great shortages of officers. Officially, the blame was placed on the middle-class for not wanting to wade through the army’s prejudices.[2] Even up until 1918, regiments tried to keep up the illusion of a “noble” officer corps with a personal relationship to the king.

Step 2 -- Get a regimental colonel to sponsor you

Sponsorship was key and perhaps the most difficult step on the ladder. Not only was the candidate scrutinized, but also his family. Sufficient income was required as the regimental commander and the current officers did not want to accept a fiscal problem- maker. Vera von Etzel tells a touching story about how Artur v. Klingspor made it into the Kürassier-Regiment von Seydlitz (Magdeburgisches) Nr.7. The gear was very expensive at that time and a burden even for his father, Lieutenant Gen. Leo v. Klingspor. Artur’s father subsidized him and he received his commission, but the subsidization came only after his younger brother, Hans Arvid, died while in the academy. Perhaps the loss of a son required his father to make sure his surviving son was in the best.

The enormous cost of a “'fancy” regiment would keep the regiments populated by the more affluent - the “vons.”[3] The father of the candidate and his son went to a dinner to be seen by all in a one night precursor of step 8. Those who were not cadets attempted to be selected as Fahnenjunker. This rank went through several iterations in an attempt to make it more professional. Prior to 1900, the regimental commander promoted the candidates after six months to the rank of Fähnrich. After 1900, more stringent criteria were enacted in an endeavor to end nepotism, which required the candidate for Fahnenjunker to have a one-year certificate but not the Abitur. Then prior to selection, the candidate had to pass a specific written test of general knowledge. If the individual passed, he enrolled as a Fahnenjunker and was allowed to take the Fähnrich examination. In infantry and dragoon regiments, a Fahnenjunker was known as a Fahnenjunker; in other cavalry regiments, a Fahnenjunker was known as a Kornet or a Standartenjunker. In artillery regiments, the individual was called a Stückjunker. The amount of time spent as a Fahnenjunker seems to have varied a great deal. The colonel would not give final approval until the Fähnrich exam was passed or in the bag. Cramming with a tutor for the exam was a standard practice.

Step 3; Pass the Fähnrich examination

In theory, each candidate was supposed to have a Prima certificate (Primareiferzeugnis) or special dispensation to gain entry to the Fähnrich examination. Ninety percent had a Prima Certificate and seventy-five percent passed the Fähnrich exam the first time. You could take it again and few failed the second time. If indeed there was a second failure, candidates were transferred into the ranks as an enlisted soldier or Unteroffizier. In 1890, the Kaiser demanded grading leniency for this examination. If leniency failed, he used dispensations, which totaled over 1000 between 1901 and 1912.[4]

There still were failures. In 1878, eight cadets failed the exam. All eight eventually were made Fähnrich and six of them earned their commission. Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron, failed the examination and was sent to the 1st Ulan Regiment as an Unteroffizier. Eight months later, he was made a Fähnrich and eventually was commissioned. This put his date of rank behind his classmates of 1911.[5]

Step 4 -- Spend time in the ranks in the regiment

A Patent or “charakterisierter Fähnrich” was a graduate of a Kadettenschule, who served with a regiment before getting his commission. A Fahnenjunker was an officer candidate, who held a certificate from a Gymnasium, who has passed the required examination in military subjects, and served with a regiment before obtaining his commission. The non-cadet individuals who passed the Fähnrich exam and moved into the regiment as a Gemeiner (private) but were referred to as an “avantageur,” joined the cadet Fähnrichs. Officially, the title was “Officeraspirant”--that title was officially changed in 1899 to “Fahnenjunker.” He lived in the barracks for a period that varied by regiment from one to six weeks. He started as a Gemeiner and when he moved out of the barracks became a Gefreiter. Patent Fähnrich never were privates just Gefreiter. He bore all costs associated with his service like a one-year volunteer did. At this point, he could also have a civilian batman (personal servant).[6]

When promoted to Unteroffizier, he got to eat in the officers’ mess. At this point, he was called “Fähnrich.” A Fähnrichsvater was appointed to be his mentor. Long drinking bouts and rules of the mess were common place. While the Fähnrich was encouraged to spend freely, indebtedness was a major embarrassment for the entire mess. Step 4 passed ever more quickly. At first, it was six months and then by the turn of the century, it was three months (two if you came from a cadet school).[7] Eventually, the time in the ranks was so short folks did not learn the system. Only the reserve officers who went through the year as an OYV understood the difficulties of the lower enlisted ranks.[8]

Step 5 -- Be promoted to Fähnrich "if all went well.”

The aspirant applied to the colonel that he was “qualified” and deserved a military qualification certificate (Dienstzeugnis). If approved by the colonel and all of the officers in the regiment, he was officially promoted to Fähnrich and paid a salary. He also got to wear the silver sword knot. Initially called Portepefähnrich that title was eliminated in 1899. Between 1892 and 1894 for example, 59 percent of the cadets became Brevet Fähnrich, 10 percent Patent Fähnrich and about 33 percent were Selekta.[9]

Step 6 -- A course at the Kriegsschule.

Cadet Abitur holders, Selekta cadets, and civilian Abitur holders ,who had been university students for a year, were exempted from this requirement from the Kriegsschule. However, if you look at the ages of the attending students you see that expanded civilian education took time and money; whereas, you could skip the education and go into the commissioning system and start making money and seniority. This length of this course shortened as the need for officers became more pressing and cadets wanted their commission in a year. At the end of the course, you took the officer’s exam. This course eventually went from twelve to seven months in length.[10]

Step 7 -- Pass officer examination and return to regiment.

Selekta Cadets went straight to step 10 if they passed the officer exam. Passing was not a problem (98 percent passed with re-take option). If indeed you did fail, you entered the army as a Fähnrich.[11] Obedience and attitude came before grades. The officers’ examination was considered far easier than the Fähnrich exam.[12] At the regiment, the Fähnrich waited (briefly) for a vacancy and to complete the next steps.

Step 8 -- Regimental officers balloted to see if they agreed to accept the candidate.

Selekta cadets did not have to undergo this. Majority vetoes were final and were sent to the King for decision. If you failed, you were either sent to another regiment for another try or to the reserves with a major stigma. Few candidates failed, as it required going against the colonel’s wishes. Some were rejected because of a lack of personal wealth, in which case the candidate was sent to another regiment without stigma. [13]

Step 9 -- Colonel recommends to the Kaiser promotion to second lieutenant

The Fähnrich became a second lieutenant and a member of the social elite, except if you were in the Artillery or Engineers. These two branches considered the newly commissioned as supernumeraries until they had served one (artillery) or two (pioneer) years, attended technical school, and passed a qualifying exam.[14] The nobility viewed technical schools as “schools for plumbers.”[15] Is there any question why the nobles eschewed these branches?

Step 10 -- Promotion is officially “Gazetted”[16]

There were numerous rules for seniority and backdating dates of rank. It is important to look at the different methods of commissioning and understand the pluses and minuses. Generally, the ten steps took approximately 18 months after the Obersekunda year. Therefore a Fahnenjunker, or a cadet entering as a charakterisiert Fähnrich at the age of 17, could gain a commission at the approximate age of 18 ½ years. Selekta cadets stayed in the Academy for an additional 12 months, but would be commissioned directly without a vote of officers -- a full six months faster than a Fahnenjunker or other early graduating cadet. The Prima cadets seeking the Abitur stayed in the Academy for two additional years, but still faced the vote in step eight. Originally, date of rank was 24 months after the Obersekunda year. In February 1900, royal order eliminated this penalty when the date of rank of Prima cadets was backdated to equal the same date as of the Selekta cadets. A Prima cadet now had the Abitur necessary to continue studies at the University and the same early date of rank as a Selekta.[17]

[1] (Clemente, 1992) pg 64

[2] (Clemente, 1992)pg. 207

[3] Wehrmacht-Awards thread, Prussian commissioning, 7/28/2004 Posted by Brian S.

v[4] (Clemente, 1992), pg 43

[5] (Moncure, 1993) pg 239-241

[6] (Clemente, 1992) pg 72

[7] (Clemente, 1992) pg 73-74

[8] (Clemente, 1992) pg 150-151

[9] (Clemente, 1992) pg 73-74

[10] (Clemente, 1992) pg.150

[11] (Moncure, 1993) pg. 242

[12] (Clemente, 1992) pg 150-157

[13] (Clemente, 1992) pgs 158-159

[14] (Clemente, 1992) pg 160

[15] (Clemente, 1992)pg 210

[16] (Martin, 1936) pg 16

[17] (Moncure, 1993)Pg. 168-170.

0 -

How about some band masters? This old guy is from Baden.

ps1950 by joerookery, on Flickr

and one more--This one looks pretty doubtful:

ps1949 by joerookery, on Flickr

0 -

You are far too good to me sir! But no good deed should go unpunished and I will probably give you more! Thank you.

0 -

Without allowing anyone to rest on their laurels here is a Bavarian can anyone tell me who he is? Thank you in advance.

ps1943 by joerookery, on Flickr

0

German Tactical Symbols 1914

in Germany: Imperial: Rick (Research) Lundstrom Forum for Documentation and Photographs

Posted

Thank you – I should've done this a long time ago. These diagrams did not make the publishers cut on the big book – gives you a feel though of the rest of the data inside. I found the Red Donkey to be quite eye-opening.